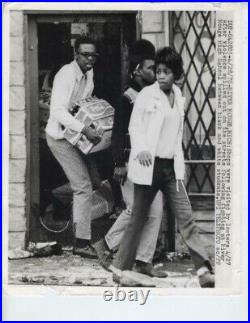

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 8X10 INCH PHOTO FROM 1970 DEPICTING RIVER ROUGE MICHIGAN LOOTERS AFTER VIOLENCE SPILLED OUT ON THE STREETS FOLLOWING FIGHTING AT RIVER ROUGE HIGH SCHOOL BETWEEN BLACK AND WHITE STUDENTS. Cur fews were ordered in two De troit suburbs after racial vio lence erupted last night and edged into Detroit today. The trouble spot are in what is called downriver Detroit – the southwest side of the city and the suburbs of River Rouge and Ecorse. Both of these downriver areas have large Negro populations. The trouble has been smol dering at half-white-half-black River Rouge High School for weeks since two members of the Board of Education entered the school and tore down post ers put up by black students for a Negro History Week last February. There have been black boycotts of the school and counter boycotts by whites. Yesterday, fighting broke out inside and outside the school, which the police broke up after using tear gas. In the evenng, crowds of Negroes looted a half-dozen stores and burned one on Visger Avenue, the dividing line between River Rouge and Ecorse. Today small crowds of blacks gathered on street corners and some minor looting occurred the police again used tear gas to disperse the crowds. Several hundred blacks gathered around Southwestern High School, a Detroit school, this morning, and there were a few fight. Students inside did not answer calls for a walk out, and after minor skirmish ing the crowds dispersed. River Rouge is a city in Wayne County in the U. The population was 7,903 at the 2010 census. It is named after the River Rouge (from the French “rouge” meaning red), which flows along the city’s northern border and into the Detroit River. The city includes the heavily industrialized Zug Island at the mouth of the River Rouge. The small settlement incorporated as a village in 1899 within Ecorse Township. [6] In 1922 as the city of Detroit expressed interest in annexing land in the township, the Village of River Rouge incorporated as a city on April 3 to avoid being annexed. [6] A month later Detroit completed annexation of land in the township immediately to the west of River Rouge. One of the most important historical associations with River Rouge is its relationship to a Great Lakes freighter, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in 1975 in a fierce storm in Lake Superior, with the loss of all 29 crew. The city had its peak of population in 1950, when industry was the mainstay of the local economy. Restructuring of heavy industry and movement of jobs offshore have taken a toll of the city; the loss of jobs resulted in loss of population. In 2015 the population is less than half of what it was in 1950. Many workers who had the flexibility to seek jobs in other areas moved away. Outward migration has resulted in a shift in the racial demographics of the city. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.24 square miles (8.39 km2), of which 2.65 square miles (6.86 km2) is land and 0.59 square miles (1.53 km2) is water. [7] Of the land area, 0.93 mi square mile (2.4 km²) consists of Zug Island. As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 7,903 people, 2,897 households, and 1,885 families living in the city. The population density was 2,982.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,151.5/km2). There were 3,731 housing units at an average density of 1,407.9 per square mile (543.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 39.4% White, 50.5% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.2% from other races, and 5.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11.2% of the population. There were 2,897 households of which 37.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 25.1% were married couples living together, 32.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 7.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.9% were non-families. 29.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.73 and the average family size was 3.37. The median age in the city was 33 years. 29.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.4% were from 25 to 44; 24.7% were from 45 to 64; and 11.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.0% male and 53.0% female. As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 9,917 people, 3,640 households, and 2,504 families living in the city. The population density was 3,713.9 per square mile (1,434.1/km²). There were 4,080 housing units at an average density of 1,528.0 per square mile (590.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 52.58% White, 42.01% African American, 0.78% Native American, 0.16% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 1.63% from other races, and 2.80% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.96% of the population. There were 3,640 households out of which 36.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.4% were married couples living together, 30.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.2% were non-families. 26.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.72 and the average family size was 3.25. In the city, the population was spread out with 31.2% under the age of 18, 10.2% from 18 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.1 males. About 19.1% of families and 22.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.6% of those under age 18 and 10.5% of those age 65 or over. A number of community resources exist in River Rouge. These include the Senior Center, Teen Center, Beechwood Center, the Walter White Community Center, the River Rouge Historical Museum and the River Rouge Public Library. In September 2015, River Rouge was selected by Gov Rick Snyder as one of 10 “Rising Tide” communities throughout the state. It is scheduled to benefit from the Michigan Department of Talent and Economic Development’s ongoing efforts and resources. River Rouge is also seeing a major push into the redevelopment of the existing housing stock, with numerous families and investors attracted to the high demand for quality family housing there. River Rouge School District serves River Rouge. Schools include River Rouge STEM Academy, Ann Visger Elementary School, Clarence B. Sabbath Elementary/Middle School, and River Rouge High School. River Rouge High School. River Rouge Public library. Jefferson Rouge River Bridge. Industrial area along the riverfront of River Rouge. N/ (listen) is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly 97,000 sq mi (250,000 km2), Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the largest by area east of the Mississippi River. [b] Its capital is Lansing, and its largest city is Detroit. Metro Detroit is among the nation’s most populous and largest metropolitan economies. Its name derives from a gallicized variant of the original Ojibwe word???? (mishigami), [7] meaning “large water” or “large lake”. Michigan consists of two peninsulas. The Lower Peninsula resembles the shape of a mitten, and comprises a majority of the state’s land area. The Upper Peninsula often called the U. Is separated from the Lower Peninsula by the Straits of Mackinac, a five-mile (8 km) channel that joins Lake Huron to Lake Michigan. The Mackinac Bridge connects the peninsulas. Michigan has the longest freshwater coastline of any political subdivision in the United States, being bordered by four of the five Great Lakes and Lake St. [9] It also has 64,980 inland lakes and ponds. The area was first occupied by a succession of Native American tribes over thousands of years. In the 17th century, French explorers claimed it as part of the New France colony, when it was largely inhabited by indigenous peoples. French and Canadian traders and settlers, Métis, and others migrated to the area, settling largely along the waterways. After France’s defeat in the French and Indian War in 1762, the region came under British rule. Britain ceded the territory to the newly independent United States after Britain’s defeat in the American Revolutionary War. The area was part of the larger Northwest Territory until 1800, when western Michigan became part of the Indiana Territory. Michigan Territory was formed in 1805, but some of the northern border with Canada was not agreed upon until after the War of 1812. Michigan was admitted into the Union in 1837 as the 26th state, a free one. It soon became an important center of industry and trade in the Great Lakes region, attracting immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries from many European countries. Immigrants from Finland, Macedonia and the Netherlands were especially numerous. Although Michigan has developed a diverse economy, in the early 20th century it became widely known as the center of the U. Automotive industry, which developed as a major national economic force. It is home to the country’s three major automobile companies (whose headquarters are all in Metro Detroit). Once exploited for logging and mining, today the sparsely populated Upper Peninsula is important for tourism due to the abundance of natural resources. [13][14] The Lower Peninsula is a center of manufacturing, forestry, agriculture, services, and high-tech industry. 20th and 21st centuries. State symbols and nicknames. Main article: History of Michigan. For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Michigan history. When the first European explorers arrived, the most populous tribes were Algonquian peoples, who include the Anishinaabe groups of Ojibwe, Odaawaa/Odawa (Ottawa), and the Boodewaadamii/Bodéwadmi (Potawatomi). The three nations co-existed peacefully as part of a loose confederation called the Council of Three Fires. The Ojibwe, whose numbers are estimated to have been between 25,000 and 35,000, were the largest. The Ojibwe Indians also known as Chippewa in the U. , an Anishaabe tribe, were established in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and northern and central Michigan. Bands also inhabited Ontario and southern Manitoba, Canada; and northern Wisconsin, and northern and north-central Minnesota. The Ottawa Indians lived primarily south of the Straits of Mackinac in northern, western, and southern Michigan, but also in southern Ontario, northern Ohio, and eastern Wisconsin. The Potawatomi were in southern and western Michigan, in addition to northern and central Indiana, northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and southern Ontario. Other Algonquian tribes in Michigan, in the south and east, were the Mascouten, the Menominee, the Miami, the Sac (or Sauk), and the Meskwaki (Fox). The Wyandot were an Iroquoian-speaking people in this area; they were historically known as the Huron by the French, and were the historical adversaries of the Iroquois Confederation. Main articles: New France and Canada (New France). Père Marquette and the Indians (1869) by Wilhelm Lamprecht. French voyageurs and coureurs des bois explored and settled in Michigan in the 17th century. The first Europeans to reach what became Michigan were those of Étienne Brûlé’s expedition in 1622. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1668 on the site where Père Jacques Marquette established Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, as a base for Catholic missions. [15][16] Missionaries in 1671-75 founded outlying stations at Saint Ignace and Marquette. Jesuit missionaries were well received by the area’s Indian populations, with few difficulties or hostilities. In 1679, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle built Fort Miami at present-day St. In 1691, the French established a trading post and Fort St. Joseph along the St. Joseph River at the present-day city of Niles. In 1701, French explorer and army officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or “Fort Pontchartrain on-the-Strait” on the strait, known as the Detroit River, between lakes Saint Clair and Erie. Cadillac had convinced King Louis XIV’s chief minister, Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, that a permanent community there would strengthen French control over the upper Great Lakes and discourage British aspirations. The hundred soldiers and workers who accompanied Cadillac built a fort enclosing one arpent[17][18] about 0.85 acres (3,400 m2), the equivalent of just under 200 feet (61 m) per side and named it Fort Pontchartrain. Cadillac’s wife, Marie Thérèse Guyon, soon moved to Detroit, becoming one of the first European women to settle in what was considered the wilderness of Michigan. The Église de Saint-Anne (Catholic Church of Saint Anne) was founded the same year. While the original building does not survive, the congregation remains active. Cadillac later departed to serve as the French governor of Louisiana from 1710 to 1716. French attempts to consolidate the fur trade led to the Fox Wars, in which the Meskwaki (Fox) and their allies fought the French and their Native allies. At the same time, the French strengthened Fort Michilimackinac at the Straits of Mackinac to better control their lucrative fur-trading empire. By the mid-18th century, the French also occupied forts at present-day Niles and Sault Ste. Marie, though most of the rest of the region remained unsettled by Europeans. France offered free land to attract families to Detroit, which grew to 800 people in 1765. It was the largest city between Montreal and New Orleans. [19] French settlers also established small farms south of the Detroit River opposite the fort, near a Jesuit mission and Huron village. Map of British America showing the original boundaries of the Province of Quebec and its Quebec Act of 1774 post-annexation boundaries. Treaty of Paris, by Benjamin West (1783), an unfinished painting of the American diplomatic negotiators of the Treaty of Paris which brought official conclusion to the Revolutionary War and gave possession of Michigan and other territory to the new United States. From 1660 until the end of French rule, Michigan was part of the Royal Province of New France. Under the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Michigan and the rest of New France east of the Mississippi River were ceded by defeated France to Great Britain. [20] After the Quebec Act was passed in 1774, Michigan became part of the British Province of Quebec. By 1778, Detroit’s population reached 2,144 and it was the third-largest city in Quebec province. During the American Revolutionary War, Detroit was an important British supply center. Most of the inhabitants were French-Canadians or American Indians, many of whom had been allied with the French because of long trading ties. Because of imprecise cartography and unclear language defining the boundaries in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the British retained control of Detroit and Michigan after the American Revolution. When Quebec split into Lower and Upper Canada in 1791, Michigan was part of Kent County, Upper Canada. It held its first democratic elections in August 1792 to send delegates to the new provincial parliament at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). Under terms negotiated in the 1794 Jay Treaty, Britain withdrew from Detroit and Michilimackinac in 1796. It retained control of territory east and south of the Detroit River, which are now included in Ontario, Canada. Questions remained over the boundary for many years, and the United States did not have uncontested control of the Upper Peninsula and Drummond Island until 1818 and 1847, respectively. Main articles: Indiana Territory, Organic act § List of organic acts, Michigan Territory, Admission to the Union, List of U. States by date of admission to the Union, and Michigan in the American Civil War. Territorial changes of the Michigan Territory from 1818 to 1836. During the War of 1812, the United States forces at Fort Detroit surrendered Michigan Territory (effectively consisting of Detroit and the surrounding area) after a nearly bloodless siege in 1812. A US attempt to retake Detroit resulted in a severe American defeat in the River Raisin Massacre. This battle, still ranked as the bloodiest ever fought in the state, had the highest number of American casualties of any battle of the war. Michigan was recaptured by the Americans in 1813 after the Battle of Lake Erie. They used Michigan as a base to launch an invasion of Canada, which culminated in the Battle of the Thames. But the more northern areas of Michigan were held by the British until the peace treaty restored the old boundaries. A number of forts, including Fort Wayne, were built by the United States in Michigan during the 19th century out of fears of renewed fighting with Britain. Michigan Territory governor and judges established the University of Michigan in 1817, as the Catholepistemiad, or the University of Michigania. The population grew slowly until the opening in 1825 of the Erie Canal through the Mohawk Valley in New York, connecting the Great Lakes to the Hudson River and New York City. The new route attracted a large influx of settlers to the Michigan territory. By the 1830s, Michigan had 80,000 residents, more than enough to apply and qualify for statehood. A Constitutional Convention of Assent was held to lead the territory to statehood. [23] In October 1835 the people approved the Constitution of 1835, thereby forming a state government. Congressional recognition was delayed pending resolution of a boundary dispute with Ohio known as the Toledo War. Congress awarded the “Toledo Strip” to Ohio. Michigan received the western part of the Upper Peninsula as a concession and formally entered the Union as a free state on January 26, 1837. The Upper Peninsula proved to be a rich source of lumber, iron, and copper. Michigan led the nation in lumber production from the 1850s to the 1880s. Railroads became a major engine of growth from the 1850s onward, with Detroit the chief hub. A second wave of French-Canadian immigrants settled in Michigan during the late 19th to early 20th century, working in lumbering areas in counties on the Lake Huron side of the Lower Peninsula, such as the Saginaw Valley, Alpena, and Cheboygan counties, as well as throughout the Upper Peninsula, with large concentrations in Escanaba and the Keweenaw Peninsula. [24] This was also a period of development of the gypsum industry in Alabaster, Michigan, which became nationally prominent. The first statewide meeting of the Republican Party took place July 6, 1854, in Jackson, Michigan, where the party adopted its platform. The state was predominately Republican until the 1930s, reflecting the political continuity of migrants from across the Northern Tier of New England and New York. Michigan made a significant contribution to the Union in the American Civil War and sent more than forty regiments of volunteers to the federal armies. Michigan modernized and expanded its system of education in this period. The Michigan State Normal School, now Eastern Michigan University, was founded in 1849, for the training of teachers. It was the fourth oldest normal school in the United States and the first U. Normal school outside New England. In 1899, the Michigan State Normal School became the first normal school in the nation to offer a four-year curriculum. Michigan Agricultural College (1855), now Michigan State University in East Lansing, was founded as the first agricultural college in the nation. Many private colleges were founded as well, and the smaller cities established high schools late in the century. Michigan’s economy underwent a transformation at the turn of the 20th century. Many individuals, including Ransom E. Olds, John and Horace Dodge, Henry Leland, David Dunbar Buick, Henry Joy, Charles King, and Henry Ford, provided the concentration of engineering know-how and technological enthusiasm to develop the automotive industry. [26] Ford’s development of the moving assembly line in Highland Park marked a new era in transportation. Like the steamship and railroad, mass production of automobiles was a far-reaching development. More than the forms of public transportation, the affordable automobile transformed private life. Automobile production became the major industry of Detroit and Michigan, and permanently altered the socioeconomic life of the United States and much of the world. With the growth, the auto industry created jobs in Detroit that attracted immigrants from Europe and migrants from across the United States, including both blacks and whites from the rural South. By 1920, Detroit was the fourth-largest city in the US. Residential housing was in short supply, and it took years for the market to catch up with the population boom. By the 1930s, so many immigrants had arrived that more than 30 languages were spoken in the public schools, and ethnic communities celebrated in annual heritage festivals. Over the years immigrants and migrants contributed greatly to Detroit’s diverse urban culture, including popular music trends. The influential Motown Sound of the 1960s was led by a variety of individual singers and groups. Grand Rapids, the second-largest city in Michigan, is also an important center of manufacturing. Since 1838, the city has been noted for its furniture industry. In the 21st century, it is home to five of the world’s leading office furniture companies. Grand Rapids is home to a number of major companies including Steelcase, Amway, and Meijer. Grand Rapids is also an important center for GE Aviation Systems. Michigan held its first United States presidential primary election in 1910. With its rapid growth in industry, it was an important center of industry-wide union organizing, such as the rise of the United Auto Workers. Throughout that decade, some of the country’s largest and most ornate skyscrapers were built in the city. Particularly noteworthy are the Fisher Building, Cadillac Place, and the Guardian Building, each of which has been designated as a National Historic Landmark (NHL). In 1927 a school bombing took place in Clinton County. The Bath School disaster, perpetrated by an adult man, resulted in the deaths of 38 schoolchildren and constitutes the deadliest mass murder in a school in U. Detroit in the mid-twentieth century. At the time, the city was the fourth-largest U. Metropolis by population, and held about one-third of the state’s population. Michigan converted much of its manufacturing to satisfy defense needs during World War II; it manufactured 10.9 percent of the United States military armaments produced during the war, ranking second (behind New York) among the 48 states. Detroit continued to expand through the 1950s, at one point doubling its population in a decade. After World War II, housing was developed in suburban areas outside city cores to meet demand for residences. The federal government subsidized the construction of interstate highways, which were intended to strengthen military access, but also allowed commuters and business traffic to travel the region more easily. Since 1960, modern advances in the auto industry have led to increased automation, high-tech industry, and increased suburban growth. Michigan is the leading auto-producing state in the US, with the industry primarily located throughout the Midwestern United States; Ontario, Canada; and the Southern United States. [28] With almost ten million residents, Michigan is a large and influential state, ranking tenth in population among the fifty states. Detroit is the centrally located metropolitan area of the Great Lakes Megalopolis and the second-largest metropolitan area in the U. (after Chicago) linking the Great Lakes system. The Metro Detroit area in Southeast Michigan is the state’s largest metropolitan area (roughly 50% of the population resides there) and the eleventh largest in the United States. The Grand Rapids metropolitan area in Western Michigan is the state’s fastest-growing metro area, with more than 1.3 million residents as of 2006. Metro Detroit receives more than 15 million visitors each year. Michigan has many popular tourist destinations, including areas such as Frankenmuth in The Thumb, and Traverse City on the Grand Traverse Bay in Northern Michigan. Michigan typically ranks third or fourth in overall Research & development (R&D) expenditures in the US. [30][31] The state’s leading research institutions include the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, and Wayne State University, which are important partners in the state’s economy and the state’s University Research Corridor. [33] Agriculture also serves a significant role, making the state a leading grower of fruit in the US, including blueberries, cherries, apples, grapes, and peaches. See also: List of Governors of Michigan and United States congressional delegations from Michigan. Main article: Government of Michigan. The Michigan State Capitol in Lansing houses the legislative branch of the government of the U. Michigan is governed as a republic, with three branches of government: the executive branch consisting of the Governor of Michigan and the other independently elected constitutional officers; the legislative branch consisting of the House of Representatives and Senate; and the judicial branch. The Michigan Constitution allows for the direct participation of the electorate by statutory initiative and referendum, recall, and constitutional initiative and referral Article II, § 9, [35] defined as the power to propose laws and to enact and reject laws, called the initiative, and the power to approve or reject laws enacted by the legislature, called the referendum. The power of initiative extends only to laws which the legislature may enact under this constitution. Lansing is the state capital and is home to all three branches of state government. The floor of the Michigan House of Representatives. The governor and the other state constitutional officers serve four-year terms and may be re-elected only once. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer. Michigan has two official Governor’s Residences; one is in Lansing, and the other is at Mackinac Island. The other constitutionally elected executive officers are the lieutenant governor, who is elected on a joint ticket with the governor, the secretary of state, and the attorney general. The lieutenant governor presides over the Senate (voting only in case of a tie) and is also a member of the cabinet. The secretary of state is the chief elections officer and is charged with running many licensure programs including motor vehicles, all of which are done through the branch offices of the secretary of state. The Michigan Legislature consists of a 38-member Senate and 110-member House of Representatives. Members of both houses of the legislature are elected through first past the post elections by single-member electoral districts of near-equal population that often have boundaries which coincide with county and municipal lines. Senators serve four-year terms concurrent to those of the governor, while representatives serve two-year terms. The Michigan State Capitol was dedicated in 1879 and has hosted the executive and legislative branches of the state ever since. Governor Gretchen Whitmer (D) speaking at a National Guard ceremony in 2019. The Michigan judiciary consists of two courts with primary jurisdiction (the Circuit Courts and the District Courts), one intermediate level appellate court (the Michigan Court of Appeals), and the Michigan Supreme Court. There are several administrative courts and specialized courts. District court judges are elected to terms of six years. In a few locations, municipal courts have been retained to the exclusion of the establishment of district courts. Circuit courts are also the only trial courts in the State of Michigan which possess the power to issue equitable remedies. Circuit courts have appellate jurisdiction from district and municipal courts, as well as from decisions and decrees of state agencies. Most counties have their own circuit court, but sparsely populated counties often share them. Circuit court judges are elected to terms of six years. State appellate court judges are elected to terms of six years, but vacancies are filled by an appointment by the governor. There are four divisions of the Court of Appeals in Detroit, Grand Rapids, Lansing, and Marquette. Cases are heard by the Court of Appeals by panels of three judges, who examine the application of the law and not the facts of the case unless there has been grievous error pertaining to questions of fact. The Michigan Supreme Court consists of seven members who are elected on non-partisan ballots for staggered eight-year terms. The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction only in narrow circumstances but holds appellate jurisdiction over the entire state judicial system. Main article: Law of Michigan. Michigan Supreme Court at the Hall of Justice. Michigan has had four constitutions, the first of which was ratified on October 5 and 6, 1835. [36] There were also constitutions from 1850 and 1908, in addition to the current constitution from 1963. The current document has a preamble, 11 articles, and one section consisting of a schedule and temporary provisions. Michigan, like every U. State except Louisiana, has a common law legal system. Main article: Politics of Michigan. Having been a Democratic-leaning state at the presidential level since the 1990s, Michigan has evolved into a swing state after Donald Trump won the state in 2016. Governors since the 1970s have alternated between the Democrats and Republicans, and statewide offices including attorney general, secretary of state, and senator have been held by members of both parties in varying proportion. Additionally, since 1994, the governor-elect has always come from the party opposite the presidency. The Republican Party holds a majority in both the House and Senate of the Michigan Legislature. The state’s congressional delegation is commonly split, with one party or the other typically holding a narrow majority. Michigan was the home of Gerald Ford, the 38th president of the United States. Born in Nebraska, he moved as an infant to Grand Rapids. [37][38] The Gerald R. Ford Museum is in Grand Rapids, and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library is on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. In a 2020 study, Michigan was ranked as the 13th easiest state for citizens to vote in. Main article: Administrative divisions of Michigan. See also: List of counties in Michigan and List of municipalities in Michigan. State government is decentralized among three tiers-statewide, county and township. Counties are administrative divisions of the state, and townships are administrative divisions of a county. Both of them exercise state government authority, localized to meet the particular needs of their jurisdictions, as provided by state law. There are 83 counties in Michigan. Cities, state universities, and villages are vested with home rule powers of varying degrees. Home rule cities can generally do anything not prohibited by law. The fifteen state universities have broad power and can do anything within the parameters of their status as educational institutions that is not prohibited by the state constitution. Villages, by contrast, have limited home rule and are not completely autonomous from the county and township in which they are located. There are two types of township in Michigan: general law township and charter. Charter township status was created by the Legislature in 1947 and grants additional powers and stream-lined administration in order to provide greater protection against annexation by a city. As of April 2001, there were 127 charter townships in Michigan. In general, charter townships have many of the same powers as a city but without the same level of obligations. For example, a charter township can have its own fire department, water and sewer department, police department, and so on-just like a city-but it is not required to have those things, whereas cities must provide those services. Charter townships can opt to use county-wide services instead, such as deputies from the county sheriff’s office instead of a home-based force of ordinance officers. Largest cities or towns in Michigan. Further information: Geography of Michigan, Protected areas of Michigan, and List of Michigan state parks. Map of the Saint Lawrence River/Great Lakes Watershed in North America. Its drainage area includes the Great Lakes, the world’s largest system of freshwater lakes. The basin covers nearly all of Michigan. The Huron National Wildlife Refuge, one of the fifteen federal wildernesses in Michigan. Michigan consists of two peninsulas separated by the Straits of Mackinac. The 45th parallel north runs through the state, marked by highway signs and the Polar-Equator Trail-[41][self-published source]along a line including Mission Point Light near Traverse City, the towns of Gaylord and Alpena in the Lower Peninsula and Menominee in the Upper Peninsula. With the exception of two tiny areas drained by the Mississippi River by way of the Wisconsin River in the Upper Peninsula and by way of the Kankakee-Illinois River in the Lower Peninsula, Michigan is drained by the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed and is the only state with the majority of its land thus drained. No point in the state is more than six miles (9.7 km) from a natural water source or more than 85 miles (137 km) from a Great Lakes shoreline. [42][better source needed]. The Great Lakes that border Michigan from east to west are Lake Erie, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan and Lake Superior. The state is bounded on the south by the states of Ohio and Indiana, sharing land and water boundaries with both. Michigan’s western boundaries are almost entirely water boundaries, from south to north, with Illinois and Wisconsin in Lake Michigan; then a land boundary with Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula, that is principally demarcated by the Menominee and Montreal Rivers; then water boundaries again, in Lake Superior, with Wisconsin and Minnesota to the west, capped around by the Canadian province of Ontario to the north and east. The heavily forested Upper Peninsula is relatively mountainous in the west. The Porcupine Mountains, which are part of one of the oldest mountain chains in the world, [43] rise to an altitude of almost 2,000 feet (610 m) above sea level and form the watershed between the streams flowing into Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. The surface on either side of this range is rugged. The state’s highest point, in the Huron Mountains northwest of Marquette, is Mount Arvon at 1,979 feet (603 m). The peninsula is as large as Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island combined but has fewer than 330,000 inhabitants. They are sometimes called “Yoopers” from U. Ers”, and their speech (the “Yooper dialect) has been heavily influenced by the numerous Scandinavian and Canadian immigrants who settled the area during the lumbering and mining boom of the late 19th century. Mackinac Island, an island and resort area at the eastern end of the Straits of Mackinac. More than 80% of the island is preserved as Mackinac Island State Park. Sleeping Bear Dunes, along the northwest coast of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. The Tahquamenon Falls in the Upper Peninsula. The Pointe Mouillee State Game Area, one of the 221 state game and wildlife areas in Michigan. It encompasses 7,483 acres of hunting, recreational, and protected wildlife and wetland areas at the mouth of the Huron River at Lake Erie, as well as smaller outlying areas within the Detroit River. The Lower Peninsula is shaped like a mitten and many residents hold up a hand to depict where they are from. [44] It is 277 miles (446 km) long from north to south and 195 miles (314 km) from east to west and occupies nearly two-thirds of the state’s land area. The surface of the peninsula is generally level, broken by conical hills and glacial moraines usually not more than a few hundred feet tall. It is divided by a low water divide running north and south. The larger portion of the state is on the west of this and gradually slopes toward Lake Michigan. The highest point in the Lower Peninsula is either Briar Hill at 1,705 feet (520 m), or one of several points nearby in the vicinity of Cadillac. The lowest point is the surface of Lake Erie at 571 feet (174 m). The geographic orientation of Michigan’s peninsulas makes for a long distance between the ends of the state. Ironwood, in the far western Upper Peninsula, lies 630 miles (1,010 kilometers) by highway from Lambertville in the Lower Peninsula’s southeastern corner. The geographic isolation of the Upper Peninsula from Michigan’s political and population centers makes the region culturally and economically distinct. Frequent attempts to establish the Upper Peninsula as its own state called “Superior” have failed to gain traction. A feature of Michigan that gives it the distinct shape of a mitten is the Thumb. This peninsula projects out into Lake Huron and the Saginaw Bay. The geography of the Thumb is mainly flat with a few rolling hills. Other peninsulas of Michigan include the Keweenaw Peninsula, making up the Copper Country region of the state. The Leelanau Peninsula lies in the Northern Lower Michigan region. See Also Michigan Regions. Numerous lakes and marshes mark both peninsulas, and the coast is much indented. Keweenaw Bay, Whitefish Bay, and the Big and Little Bays De Noc are the principal indentations on the Upper Peninsula. The Grand and Little Traverse, Thunder, and Saginaw bays indent the Lower Peninsula. Michigan has the second longest shoreline of any state-3,288 miles (5,292 km), [45] including 1,056 miles (1,699 km) of island shoreline. The state has numerous large islands, the principal ones being the North Manitou and South Manitou, Beaver, and Fox groups in Lake Michigan; Isle Royale and Grande Isle in Lake Superior; Marquette, Bois Blanc, and Mackinac islands in Lake Huron; and Neebish, Sugar, and Drummond islands in St. Michigan has about 150 lighthouses, the most of any U. The first lighthouses in Michigan were built between 1818 and 1822. See Lighthouses in the United States. The state’s rivers are generally small, short and shallow, and few are navigable. The principal ones include the Detroit River, St. Marys River, and St. Clair River which connect the Great Lakes; the Au Sable, Cheboygan, and Saginaw, which flow into Lake Huron; the Ontonagon, and Tahquamenon, which flow into Lake Superior; and the St. Joseph, Kalamazoo, Grand, Muskegon, Manistee, and Escanaba, which flow into Lake Michigan. The state has 11,037 inland lakes-totaling 1,305 square miles (3,380 km2) of inland water-in addition to 38,575 square miles (99,910 km2) of Great Lakes waters. No point in Michigan is more than six miles (9.7 km) from an inland lake or more than 85 miles (137 km) from one of the Great Lakes. The state is home to several areas maintained by the National Park Service including: Isle Royale National Park, in Lake Superior, about 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Other national protected areas in the state include: Keweenaw National Historical Park, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Huron National Forest, Manistee National Forest, Hiawatha National Forest, Ottawa National Forest and Father Marquette National Memorial. The largest section of the North Country National Scenic Trail passes through Michigan. With 78 state parks, 19 state recreation areas, and six state forests, Michigan has the largest state park and state forest system of any state. See also: Climate change in Michigan. Michigan has a continental climate, although there are two distinct regions. The southern and central parts of the Lower Peninsula (south of Saginaw Bay and from the Grand Rapids area southward) have a warmer climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with hot summers and cold winters. The northern part of Lower Peninsula and the entire Upper Peninsula has a more severe climate (Köppen Dfb), with warm, but shorter summers and longer, cold to very cold winters. Some parts of the state average high temperatures below freezing from December through February, and into early March in the far northern parts. During the winter through the middle of February, the state is frequently subjected to heavy lake-effect snow. The state averages from 30 to 40 inches (76 to 102 cm) of precipitation annually; however, some areas in the northern lower peninsula and the upper peninsula average almost 160 inches (4,100 mm) of snowfall per year. [48] Michigan’s highest recorded temperature is 112 °F (44 °C) at Mio on July 13, 1936, and the coldest recorded temperature is -51 °F (-46 °C) at Vanderbilt on February 9, 1934. The state averages 30 days of thunderstorm activity per year. These can be severe, especially in the southern part of the state. The state averages 17 tornadoes per year, which are more common in the state’s extreme southern section. Portions of the southern border have been almost as vulnerable historically as states further west and in Tornado Alley. For this reason, many communities in the very southern portions of the state have tornado sirens to warn residents of approaching tornadoes. Farther north, in Central Michigan, Northern Michigan, and the Upper Peninsula, tornadoes are rare. The geological formation of the state is greatly varied, with the Michigan Basin being the most major formation. Primary boulders are found over the entire surface of the Upper Peninsula (being principally of primitive origin), while Secondary deposits cover the entire Lower Peninsula. The Upper Peninsula exhibits Lower Silurian sandstones, limestones, copper and iron bearing rocks, corresponding to the Huronian system of Canada. The central portion of the Lower Peninsula contains coal measures and rocks of the Pennsylvanian period. Devonian and sub-Carboniferous deposits are scattered over the entire state. Michigan rarely experiences earthquakes, and those that it does experience are generally smaller ones that do not cause significant damage. A 4.6-magnitude earthquake struck in August 1947. More recently, a 4.2-magnitude earthquake occurred on Saturday, May 2, 2015, shortly after noon, about five miles south of Galesburg, Michigan (9 miles southeast of Kalamazoo) in central Michigan, about 140 miles west of Detroit, according to the Colorado-based U. Geological Survey’s National Earthquake Information Center. No major damage or injuries were reported, according to Governor Rick Snyder’s office. See also: Michigan statistical areas. Michigan 2020 population distribution. Racial Composition of Michigan (as of 2010). Hispanic and Latino (of any race). Black or African American. Two or more races. Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. The United States Census Bureau recorded the population of Michigan at 10,084,442 at the 2020 United States Census, an increase of 2.03% from 9,883,635 recorded at the 2010 United States Census. The center of population of Michigan is in Shiawassee County, in the southeastern corner of the civil township of Bennington, which is northwest of the village of Morrice. As of the 2010 American Community Survey for the U. Census, the state had a foreign-born population of 592,212, or 6.0% of the total. Michigan has the largest Dutch, Finnish, and Macedonian populations in the United States. Michigan racial breakdown of population. Thirteen largest ancestries in Michigan (2016)[59]. The large majority of Michigan’s population is white. Americans of European descent live throughout Michigan and most of Metro Detroit. Large European American groups include those of German, British, Irish, Polish and Belgian ancestry. People of Scandinavian descent, and those of Finnish ancestry, have a notable presence in the Upper Peninsula. Western Michigan is known for the Dutch heritage of many residents (the highest concentration of any state), especially in Holland and metropolitan Grand Rapids. African-Americans, who came to Detroit and other northern cities in the Great Migration of the early 20th century, form a majority of the population of the city of Detroit and of other cities, including Flint and Benton Harbor. As of 2007 about 300,000 people in Southeastern Michigan trace their descent from the Middle East. [60] Dearborn has a sizeable Arab community, with many Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac, and Lebanese who immigrated for jobs in the auto industry in the 1920s along with more recent Yemenis and Iraqis. As of 2007, almost 8,000 Hmong people lived in the State of Michigan, about double their 1999 presence in the state. [62] As of 2007 most lived in northeastern Detroit, but they had been increasingly moving to Pontiac and Warren. [63] By 2015 the number of Hmong in the Detroit city limits had significantly declined. [64] Lansing hosts a statewide Hmong New Year Festival. [63] The Hmong community also had a prominent portrayal in the 2008 film Gran Torino, which was set in Detroit. As of 2015, 80% of Michigan’s Japanese population lived in the counties of Macomb, Oakland, Washtenaw, and Wayne in the Detroit and Ann Arbor areas. [65] As of April 2013, the largest Japanese national population is in Novi, with 2,666 Japanese residents, and the next largest populations are respectively in Ann Arbor, West Bloomfield Township, Farmington Hills, and Battle Creek. The state has 481 Japanese employment facilities providing 35,554 local jobs. 391 of them are in Southeast Michigan, providing 20,816 jobs, and the 90 in other regions in the state provide 14,738 jobs. The Japanese Direct Investment Survey of the Consulate-General of Japan, Detroit stated more than 2,208 additional Japanese residents were employed in the State of Michigan as of 1 October 2012, than in 2011. [66] During the 1990s the Japanese population of Michigan experienced an increase, and many Japanese people with children moved to particular areas for their proximity to Japanese grocery stores and high-performing schools. A person from Michigan is called a Michigander or Michiganian;[67] also at times, but rarely, a “Michiganite”. [68] Residents of the Upper Peninsula are sometimes referred to as “Yoopers” a phonetic pronunciation of U. Ers”, and they sometimes refer to those from the Lower Peninsula as “trolls because they live below the bridge (see Three Billy Goats Gruff). As of 2011, 34.3% of Michigan’s children under the age of one belonged to racial or ethnic minority groups, meaning they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white. Note: Percentages in the table can exceed 100% as Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race. Live births by single race/ethnicity of mother. Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race. As of 2010, 91.11% (8,507,947) of Michigan residents age five and older spoke only English at home, while 2.93% (273,981) spoke Spanish, 1.04% (97,559) Arabic, 0.44% (41,189) German, 0.36% (33,648) Chinese (which includes Mandarin), 0.31% (28,891) French, 0.29% (27,019) Polish, and Syriac languages (such as Modern Aramaic and Northeastern Neo-Aramaic) was spoken as a main language by 0.25% (23,420) of the population over the age of five. In total, 8.89% (830,281) of Michigan’s population age five and older spoke a mother language other than English. Most common non-English languages spoken in Michigan. The Basilica of Sainte Anne de Détroit is the second-oldest continuously operating Roman Catholic parish in the country. The Roman Catholic Church has six dioceses and one archdiocese in Michigan; Gaylord, Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, Lansing, Marquette, Saginaw and Detroit. [82] The Roman Catholic Church is the largest denomination by number of adherents, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) 2010 survey, with 1,717,296 adherents. [83] The Roman Catholic Church was the only organized religion in Michigan until the 19th century, reflecting the territory’s French colonial roots. Detroit’s Saint Anne’s parish, established in 1701 by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, is the second-oldest Roman Catholic parish in the United States. [84] On March 8, 1833, the Holy See formally established a diocese in the Michigan territory, which included all of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas east of the Mississippi River. When Michigan became a state in 1837, the boundary of the Diocese of Detroit was redrawn to coincide with that of the State; the other dioceses were later carved out from the Diocese of Detroit but remain part of the Ecclesiastical Province of Detroit. In 2010, the largest Protestant denominations were the United Methodist Church with 228,521 adherents; followed by the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod with 219,618, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America with 120,598 adherents. The Christian Reformed Church in North America had almost 100,000 members and more than 230 congregations in Michigan. [86] The Reformed Church in America had 76,000 members and 154 congregations in the state. [87] In the same survey, Jewish adherents in the state of Michigan were estimated at 44,382, and Muslims at 120,351. [88] The Lutheran Church was introduced by German and Scandinavian immigrants; Lutheranism is the second largest religious denomination in the state. The first Jewish synagogue in the state was Temple Beth El, founded by twelve German Jewish families in Detroit in 1850. In West Michigan, Dutch immigrants fled from the specter of religious persecution and famine in the Netherlands around 1850 and settled in and around what is now Holland, Michigan, establishing a “colony” on American soil that fervently held onto Calvinist doctrine that established a significant presence of Reformed churches. [90] Islam was introduced by immigrants from the Near East during the 20th century. [91] Michigan is home to the largest mosque in North America, the Islamic Center of America in Dearborn. Battle Creek, Michigan, is also the birthplace of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which was founded on May 21, 1863. Religious affiliation in Michigan (2014)[94]. See also: List of companies based in Michigan, Economy of metropolitan Detroit, and Michigan locations by per capita income. With State and U. List of Michigan companies. The Ambassador Bridge, a suspension bridge that connects Detroit with Windsor, Ontario, in Canada. It is the busiest international border crossing in North America in terms of trade volume. Michigan is the center of the American automotive industry. The Renaissance Center in Downtown Detroit is the world headquarter of General Motors. Ford Dearborn Proving Ground (DPG) completed major reconstruction and renovations in 2006. In 2017, 3,859,949 people in Michigan were employed at 222,553 establishments, according to the U. [97] According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of June 2021, the state’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was estimated at 6.3%. Products and services include automobiles, food products, information technology, aerospace, military equipment, furniture, and mining of copper and iron ore. [quantify] Michigan is the third leading grower of Christmas trees with 60,520 acres (245 km2) of land dedicated to Christmas tree farming. [99][100] The beverage Vernors was invented in Michigan in 1866, sharing the title of oldest soft drink with Hires Root Beer. Faygo was founded in Detroit on November 4, 1907. Two of the top four pizza chains were founded in Michigan and are headquartered there: Domino’s Pizza by Tom Monaghan and Little Caesars Pizza by Mike Ilitch. Michigan became the 24th right-to-work state in U. Since 2009, GM, Ford and Chrysler have managed a significant reorganization of their benefit funds structure after a volatile stock market which followed the September 11 attacks and early 2000s recession impacted their respective U. Pension and benefit funds (OPEB). [101] General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler reached agreements with the United Auto Workers Union to transfer the liabilities for their respective health care and benefit funds to a 501(c)(9) Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA). Manufacturing in the state grew 6.6% from 2001 to 2006, [102] but the high speculative price of oil became a factor for the U. Auto industry during the economic crisis of 2008 impacting industry revenues. In 2009, GM and Chrysler emerged from Chapter 11 restructurings with financing provided in part by the U. [103][104] GM began its initial public offering (IPO) of stock in 2010. [105] For 2010, the Big Three domestic automakers have reported significant profits indicating the beginning of rebound. [106][107][108][109]. As of 2002, Michigan ranked fourth in the U. In high tech employment with 568,000 high tech workers, which includes 70,000 in the automotive industry. [110] Michigan typically ranks third or fourth in overall research and development (R&D) expenditures in the United States. [30][31] Its research and development, which includes automotive, comprises a higher percentage of the state’s overall gross domestic product than for any other U. [111] The state is an important source of engineering job opportunities. The domestic auto industry accounts directly and indirectly for one of every ten jobs in the U. Michigan was second in the U. In 2004 for new corporate facilities and expansions. From 1997 to 2004, Michigan was the only state to top the 10,000 mark for the number of major new developments;[28][113] however, the effects of the late 2000s recession have slowed the state’s economy. In 2008, Michigan placed third in a site selection survey among the states for luring new business which measured capital investment and new job creation per one million population. Department of Energy for the manufacture of electric vehicle technologies which is expected to generate 6,800 immediate jobs and employ 40,000 in the state by 2020. [115] From 2007 to 2009, Michigan ranked 3rd in the U. For new corporate facilities and expansions. As leading research institutions, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, and Wayne State University are important partners in the state’s economy and its University Research Corridor. [33] The National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory is at Michigan State University. Michigan’s workforce is well-educated and highly skilled, making it attractive to companies. It has the third highest number of engineering graduates nationally. Detroit Metropolitan Airport is one of the nation’s most recently expanded and modernized airports with six major runways, and large aircraft maintenance facilities capable of servicing and repairing a Boeing 747 and is a major hub for Delta Air Lines. Michigan’s schools and colleges rank among the nation’s best. The state has maintained its early commitment to public education. The state’s infrastructure gives it a competitive edge; Michigan has 38 deep water ports. Michigan led the nation in job creation improvement in 2010. A treemap depicting the distribution of Michigan’s jobs as percentages of entire workforce. Distribution of Michigan’s jobs as percentages of entire workforce. See also: Cherry production in Michigan. Michigan is the leading U. Producer of tart cherries, blueberries, pickling cucumbers, navy beans and petunias. The world headquarters of the Kellogg’s Company in Battle Creek. A wide variety of commodity crops, fruits, and vegetables are grown in Michigan, making it second only to California among U. States in the diversity of its agriculture. [128] The most valuable agricultural product is milk. Leading crops include corn, soybeans, flowers, wheat, sugar beets, and potatoes. Livestock in the state included 78,000 sheep, a million cattle, a million hogs, and more than three million chickens. Livestock products accounted for 38% of the value of agricultural products while crops accounted for the majority. Michigan is a leading grower of fruit in the U. Including blueberries, tart cherries, apples, grapes, and peaches. [34][129] Plums, pears, and strawberries are also grown in Michigan. These fruits are mainly grown in West Michigan due to the moderating effect of Lake Michigan on the climate. There is also significant fruit production, especially cherries, but also grapes, apples, and other fruits, in Northwest Michigan along Lake Michigan. Michigan produces wines, beers and a multitude of processed food products. Kellogg’s cereal is based in Battle Creek, Michigan and processes many locally grown foods. Thornapple Valley, Ball Park Franks, Koegel Meat Company, and Hebrew National sausage companies are all based in Michigan. Michigan is home to very fertile land in the Saginaw Valley and Thumb areas. Products grown there include corn, sugar beets, navy beans, and soybeans. Sugar beet harvesting usually begins the first of October. It takes the sugar factories about five months to process the 3.7 million tons of sugarbeets into 485,000 tons of pure, white sugar. [130] Michigan’s largest sugar refiner, Michigan Sugar Company[131] is the largest east of the Mississippi River and the fourth largest in the nation. Michigan sugar brand names are Pioneer Sugar and the newly incorporated Big Chief Sugar. Potatoes are grown in Northern Michigan, and corn is dominant in Central Michigan. Alfalfa, cucumbers, and asparagus are also grown. See also: List of National Historic Landmarks in Michigan, List of Registered Historic Places in Michigan, and List of museums in Michigan. Mackinac Island is well-known for cultural events and a wide variety of architectural styles, including the Victorian Grand Hotel. Holland, Michigan, is the home of the Tulip Time Festival, the largest tulip festival in the U. [132] Michigan’s tourism website ranks among the busiest in the nation. [133] Destinations draw vacationers, hunters, and nature enthusiasts from across the United States and Canada. Michigan is 50% forest land, much of it quite remote. The forests, lakes and thousands of miles of beaches are top attractions. Event tourism draws large numbers to occasions like the Tulip Time Festival and the National Cherry Festival. In 2006, the Michigan State Board of Education mandated all public schools in the state hold their first day of school after Labor Day, in accordance with the new Post Labor Day School law. A survey found 70% of all tourism business comes directly from Michigan residents, and the Michigan Hotel, Motel, & Resort Association claimed the shorter summer between school years cut into the annual tourism season. Tourism in metropolitan Detroit draws visitors to leading attractions, especially The Henry Ford, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Zoo, and to sports in Detroit. Other museums include the Detroit Historical Museum, the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, museums in the Cranbrook Educational Community, and the Arab American National Museum. The metro area offers four major casinos, MGM Grand Detroit, Hollywood Casino, Motor City, and Caesars Windsor in Windsor, Ontario, Canada; moreover, Detroit is the largest American city and metropolitan region to offer casino resorts. Hunting and fishing are significant industries in the state. Charter boats are based in many Great Lakes cities to fish for salmon, trout, walleye, and perch. More than three-quarters of a million hunters participate in white-tailed deer season alone. Many school districts in rural areas of Michigan cancel school on the opening day of firearm deer season, because of attendance concerns. Marquette, Michigan, is home to a vast snowmobile trail system. Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources manages the largest dedicated state forest system in the nation. Public hiking and hunting access has also been secured in extensive commercial forests. The state has the highest number of golf courses and registered snowmobiles in the nation. The state has numerous historical markers, which can themselves become the center of a tour. [137] The Great Lakes Circle Tour is a designated scenic road system connecting all of the Great Lakes and the St. The Michigan Underwater Preserves are 11 underwater areas where wrecks are protected for the benefit of sport divers. See also: List of power stations in Michigan. Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station on the shore of Lake Erie near Monroe. In 2020, Michigan consumed 113,740-gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy and produced 116,700-gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy. Coal power is Michigan’s leading source of electricity, producing roughly half its supply or 53,100-gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy (12.6 GW total capacity) in 2020. [139] Although Michigan has no active coal mines, coal is easily moved from other states by train and across the Great Lakes by lake freighters. The lower price of natural gas is leading to the closure of most coal plants, with Consumer Energy planning to close all of its remaining coal plants by 2025;[140] DTE plans to retire 2100MW of coal power by 2023. [141] The coal-fired Monroe Power Plant in Monroe, on the western shore of Lake Erie, is the nation’s 11th-largest electric plant, with a net capacity of 3,400 MW. Nuclear power is also a significant source of electrical power in Michigan, producing roughly one-quarter of the state’s supply or 28,000-gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy (4.3 GW total capacity) in 2020. [139] The three active nuclear power plants supply Michigan with about 26% of its electricity. Cook Nuclear Plant, just north of Bridgman, is the state’s largest nuclear power plant, with a net capacity of 2,213 MW. The Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station is the second-largest, with a net capacity of 1,150 MW. It is also one of the two nuclear power plants in the Detroit metropolitan area (within a 50-mile radius of Detroit’s city center), about halfway between Detroit and Toledo, Ohio, the other being the Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Station, in Ottawa County, Ohio. The Palisades Nuclear Power Plant, south of South Haven, closed in May 2022. [142] The Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant, Michigan’s first nuclear power plant and the nation’s fifth, was decommissioned in 1997. The Bluewater Bridge, a twin-span bridge across the St. Clair River that links Port Huron and Sarnia, Ontario. Michigan has nine international road crossings with Ontario, Canada. Ambassador Bridge, North America’s busiest international border, crossing the Detroit River. Blue Water Bridge, a twin-span bridge (Port Huron, Michigan, and Point Edward, Ontario, but the larger city of Sarnia is usually referred to on the Canadian side). Blue Water Ferry (Marine City, Michigan, and Sombra, Ontario). Canadian Pacific Railway tunnel. Detroit-Windsor Truck Ferry (Detroit and Windsor). International Bridge Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Clair River Railway Tunnel (Port Huron and Sarnia). Walpole Island Ferry (Algonac, Michigan, and Walpole Island First Nation, Ontario). The Gordie Howe International Bridge, a second international bridge between Detroit and Windsor, is under construction. It is expected to be completed in 2024. See also: List of Michigan railroads and History of railroads in Michigan. Michigan is served by four Class I railroads: the Canadian National Railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, CSX Transportation, and the Norfolk Southern Railway. These are augmented by several dozen short line railroads. Main article: Michigan Services. Amtrak passenger rail services the state, connecting many southern and western Michigan cities to Chicago, Illinois. There are plans for commuter rail for Detroit and its suburbs (see SEMCOG Commuter Rail). See also: Michigan State Trunkline Highway System and County-Designated Highways in Michigan. US Highway 2 (US 2) runs along Lake Michigan from Naubinway to its eastern terminus at St. The Mackinac Bridge, a suspension bridge spanning the Straits of Mackinac to connect the Upper and Lower peninsulas of Michigan. Interstate 75 (I-75) is the main thoroughfare between Detroit, Flint, and Saginaw extending north to Sault Ste. Marie and providing access to Sault Ste. The freeway crosses the Mackinac Bridge between the Lower and Upper Peninsulas. Auxiliary highways include I-275 and I-375 in Detroit; I-475 in Flint; and I-675 in Saginaw. I-69 enters the state near the Michigan-Ohio-Indiana border, and it extends to Port Huron and provides access to the Blue Water Bridge crossing into Sarnia, Ontario. I-94 enters the western end of the state at the Indiana border, and it travels east to Detroit and then northeast to Port Huron and ties in with I-69. I-194 branches off from this freeway in Battle Creek. I-94 is the main artery between Chicago and Detroit. I-96 runs east-west between Detroit and Muskegon. I-496 loops through Lansing. I-196 branches off from this freeway at Grand Rapids and connects to I-94 near Benton Harbor. I-696 branches off from this freeway at Novi and connects to I-94 near St. US Highway 2 (US 2) enters Michigan at the city of Ironwood and travels east to the town of Crystal Falls, where it turns south and briefly re-enters Wisconsin northwest of Florence. It re-enters Michigan north of Iron Mountain and continues through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the cities of Escanaba, Manistique, and St. Along the way, it cuts through the Ottawa and Hiawatha national forests and follows the northern shore of Lake Michigan. Its eastern terminus lies at exit 344 on I-75, just north of the Mackinac Bridge. US Highway 23 enters Michigan at the Ohio state line in the suburban spillover of Toledo, Ohio, as a freeway and leads northward to Ann Arbor before merging with I-75 just south of Flint. Concurrent with I-75 through Flint, Saginaw, and Bay City, it splits from I-75 at Standish as an intermittently four lane/two-lane surface road closely following the western shore of Lake Huron generally northward through Alpena before turning west to northwest toward Mackinaw City and Interstate 75 again, where it terminates. US Highway 31 enters Michigan as Interstate-quality freeway at the Indiana State Line just northwest of South Bend, Indiana, heads north to Interstate 196 near Benton Harbor, and follows the eastern shore of Lake Michigan to Mackinaw City, where it has its northern terminus. US Highway 127 enters Michigan from Ohio south of Hudson as a two-lane, undivided highway and closely follows the Michigan meridian, the principal north-south line used to survey Michigan in the early 19th century. It passes north through Jackson and Lansing before terminating south of Grayling at I-75, and is a four-lane freeway for the majority of its course. US Highway 131 has its southern terminus at the Indiana Toll Road roughly one mile south of the Indiana state line as a two-lane surface road. It passes through Kalamazoo and Grand Rapids as a freeway of Interstate standard and continues as such to Manton, where it reverts to two-lane surface road to its northern terminus at US 31 in Petoskey. See also: List of airports in Michigan. Aerial view of Detroit Metro Airport (DTW). The Detroit Metropolitan Airport in the western suburb of Romulus, was in 2010 the 16th busiest airfield in North America measured by passenger traffic. [150] The Gerald R. Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids is the next busiest airport in the state, served by eight airlines to 23 destinations. Flint Bishop International Airport is the third largest airport in the state, served by four airlines to several primary hubs. Other frequently trafficked airports include Cherry Capital Airport, in Traverse City, Kalamazoo/Battle Creek International Airport, serving the Kalamazoo and Battle Creek region, Capital Region International Airport, located outside of Lansing, and MBS International Airport serving the Midland, Bay City and Saginaw tri-city region. Additionally, smaller regional and local airports are located throughout the state including on several islands. Further information: List of cities, villages, and townships in Michigan. Largest combined statistical areas in Michigan[151]. Constituent core-based statistical areas. Metro Detroit by Sentinel-2, 2021-09-06 (big version). Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Flint, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Ann Arbor, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Monroe, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Adrian, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Grand Rapids by Sentinel-2. Grand Rapids-Kentwood, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Muskegon, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Holland, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Big Rapids, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. South Bend-Mishawaka, IN-MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Elkhart-Goshen, IN Metropolitan Statistical Area. Niles, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Warsaw, IN Micropolitan Statistical Area. Plymouth, IN Micropolitan Statistical Area. Downtown Lansing, Michigan, as seen from the air early one morning in May, 2017. Lansing-East Lansing, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Owosso, MI Micropolitan statistical area. Battle Creek, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Sturgis, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Coldwater, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Saginaw, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Bay City, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Midland, MI Metropolitan Statistical Area. Mount Pleasant, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Alma, MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Marinette, WI-MI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Iron Mountain, MI-WI Micropolitan Statistical Area. Other economically significant cities include. Battle Creek, known as “Cereal City”, is the headquarters of Kellogg’s. Joseph is the headquarters of Whirlpool Corporation. East Lansing is the home of Michigan State University. Holland is the home of the Tulip Time Festival, the largest tulip festival in the U. Jackson is the headquarters of CMS Energy. Manistee is home to the world’s largest salt plant, owned by Morton Salt. Marquette is the largest city in the Upper Peninsula with 19,661 people and home of Northern Michigan University. Midland is the headquarters of the Dow Chemical Company and the Dow Corning Corporation. Marie is the home of the Soo Locks and Sault Ste. Traverse City is the “Cherry Capital of the World”, making Michigan the nation’s largest producer of cherries and is also the largest city in Northern Michigan. Half the wealthiest communities in the state are in Oakland County, just north of Detroit. Another wealthy community is just east of the city, in Grosse Pointe. Only three of these cities are outside of Metro Detroit. See also: List of colleges and universities in Michigan and List of high schools in Michigan. Michigan’s education system serves 1.6 million K-12 students in public schools. More than 124,000 students attend private schools and an uncounted number are homeschooled under certain legal requirements. [154] From 2009 to 2019, over 200 private schools in Michigan closed, partly due to competition from charter schools. The University of Michigan is the oldest higher-educational institution in the state, and among the oldest research universities in the nation. It was founded in 1817, 20 years before Michigan Territory achieved statehood. [156][157] Michigan State University has the ninth largest campus population of any U. School as of fall, 2016. With an enrollment of 21,210 students, Baker College is Michigan’s largest private post-secondary institution. The Finlandia University in Hancock, Houghton County, Michigan. Cranbrook Schools, one of the leading college preparatory boarding schools in the country. The Carnegie Foundation classifies ten of the state’s institutions (University of Michigan, Michigan State University, Wayne State University, Eastern Michigan University, Central Michigan University, Western Michigan University, Michigan Technological University, Oakland University, Andrews University, and Baker College) as research universities. Main article: Music of Michigan. Michigan music is known for three music trends: early punk rock, Motown/soul music and techno music. Michigan musicians include Tally Hall, Bill Haley & His Comets, The Supremes, The Marvelettes, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye “The Prince of Soul”, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Aretha Franklin, Mary Wells, Tommy James and the Shondells, ? And the Mysterians, Al Green, The Spinners, Grand Funk Railroad, The Stooges, the MC5, The Knack, Madonna “The Queen of Pop”, Bob Seger, Ray Parker Jr. Aaliyah, Eminem, Kid Rock, Jack White and Meg White (The White Stripes), Big Sean, Alice Cooper, and Del Shannon. Major theaters in Michigan include the Fox Theatre, Music Hall, Gem Theatre, Masonic Temple Theatre, the Detroit Opera House, Fisher Theatre, The Fillmore Detroit, Saint Andrew’s Hall, Majestic Theater, and Orchestra Hall. The Nederlander Organization, the largest controller of Broadway productions in New York City, originated in Detroit. Main article: List of Michigan professional sports teams. See also: List of Michigan sport championships. Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor is the largest stadium in the Western Hemisphere, and the third-largest stadium in the world. Michigan’s major-league sports teams include: Detroit Tigers baseball team, Detroit Lions football team, Detroit Red Wings ice hockey team, and the Detroit Pistons men’s basketball team. All of Michigan’s major league teams play in the Metro Detroit area. The state also has a professional second-tier (USL Championship) soccer team in Detroit City FC, which plays its home games at Keyworth Stadium in Hamtramack, Michigan. The Pistons played at Detroit’s Cobo Arena until 1978 and at the Pontiac Silverdome until 1988 when they moved into The Palace of Auburn Hills. In 2017, the team moved to the newly built Little Caesars Arena in downtown Detroit. The Detroit Lions played at Tiger Stadium in Detroit until 1974, then moved to the Pontiac Silverdome where they played for 27 years between 1975 and 2002 before moving to Ford Field in Detroit in 2002. The Detroit Tigers played at Tiger Stadium (formerly known as Navin Field and Briggs Stadium) from 1912 to 1999. In 2000 they moved to Comerica Park. The Red Wings played at Olympia Stadium before moving to Joe Louis Arena in 1979. They later moved to Little Caesars Arena to join the Pistons as tenants in 2017. Professional hockey got its start in 1903 in Houghton, [161] when the Portage Lakers were formed. Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, Michigan. The Michigan International Speedway is the site of NASCAR races and Detroit was formerly the site of a Formula One World Championship Grand Prix race. From 1959 to 1961, Detroit Dragway hosted the NHRA’s U. [163] Michigan is home to one of the major canoeing marathons: the 120-mile (190 km) Au Sable River Canoe Marathon. The Port Huron to Mackinac Boat Race is also a favorite. Twenty-time Grand Slam champion Serena Williams was born in Saginaw. The 2011 World Champion for Women’s Artistic Gymnastics, Jordyn Wieber is from DeWitt. Wieber was also a member of the gold medal team at the London Olympics in 2012. Collegiate sports in Michigan are popular in addition to professional sports. The state’s two largest athletic programs are the Michigan Wolverines and Michigan State Spartans, which play in the NCAA Big Ten Conference. Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor, home to the Michigan Wolverines football team, is the largest stadium in the Western Hemisphere and the third-largest stadium worldwide. The Michigan High School Athletic Association features around 300,000 participants. Michigan is traditionally known as “The Wolverine State”, and the University of Michigan takes the wolverine as its mascot. The association is well and long established: for example, many Detroiters volunteered to fight during the American Civil War and George Armstrong Custer, who led the Michigan Brigade, called them the “Wolverines”. The origins of this association are obscure; it may derive from a busy trade in wolverine furs in Sault Ste. Marie in the 18th century or may recall a disparagement intended to compare early settlers in Michigan with the vicious mammal. Wolverines are, however, extremely rare in Michigan. A sighting in February 2004 near Ubly was the first confirmed sighting in Michigan in 200 years. [164] The animal was found dead in 2010. State nicknames: Wolverine State, Great Lake State, Mitten State, Water-Winter Wonderland. State motto: Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam circumspice (Latin: “If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you”) adopted in 1835 on the coat-of-arms, but never as an official motto. This is a paraphrase of the epitaph of British architect Sir Christopher Wren about his masterpiece, St. State song: “My Michigan” (official since 1937, but disputed amongst residents), [168] “Michigan, My Michigan” (Unofficial state song, since the civil war). State bird: American robin (since 1931). State animal: wolverine (traditional). State game animal: white-tailed deer (since 1997). State fish: brook trout (since 1965). State reptile: painted turtle (since 1995). State fossil: mastodon (since 2000). State flower: apple blossom (adopted in 1897, official in 1997). State wildflower: dwarf lake iris (since 1998) a federally listed threatened species. State tree: white pine (since 1955). State stone: Petoskey stone (since 1965). It is composed of fossilized coral (Hexagonaria pericarnata) from long ago when the middle of the continent was covered with a shallow sea. State gem: Isle Royale greenstone (since 1973). Also called chlorastrolite (literally “green star stone”), the mineral is found on Isle Royale and the Keweenaw peninsula. Coin issued in 2004 with the Michigan motto “Great Lakes State”. State soil: Kalkaska sand (since 1990), ranges in color from black to yellowish brown, covers nearly 1,000,000-acre (4,000 km2) in 29 counties. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Republic of Croatia, Malaysia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion.

- Type: Photograph

- Year of Production: 1970

- Image Color: Black & White

Posted in

Posted in